Timothy James reflects on the significance of the cross and its meaning for our lives

“The cross is the door to mysteries. Through this door the intellect makes entrance into the knowledge of heavenly mysteries. The knowledge of the cross is concealed in the sufferings of the cross.” The Ascetical Homilies of Saint Isaac of Syria

‘Deconstruction’

I wonder what comes to mind when you read the term ‘deconstruction’. This word may conjure up an immediate reaction of a positive or negative kind, or it may simply bring to mind a memory, a conversation or a picture. For each of us, this term will likely create a unique reaction. The term ‘deconstruction’ has been adopted by various groups in various circles and has, in so doing, become a catch-all term to define every and any kind of faith or religious evolution. Whether it be a complete deconstruction of a whole-life faith system or a rejection of certain doctrinal points, ‘deconstruction’ has taken on a broad, wide and varied meaning.

‘Deconstruction’ has been defined in different ways by different people for different purposes to describe different experiences. It’s a term which is often loaded with subjective meaning; whether it be positive (to affirm progress in the faith) or negative (to refer to a betrayal of certain established religious beliefs). It is a term which is used as a compliment and an insult, as a process and a destination, and as an identity and an add-on.

Much has been written and will continue to be written about the etymology of deconstruction and how the act of deconstruction contributes to the human faith experience. But this article is not concerned with the merits nor pitfalls of deconstructing a personal or corporate faith. Rather, it is focussed on exploring the centrality of deconstruction in the gospel message.

At the heart of the gospel is a message of counter-cultural, radical and ongoing deconstruction. Through the cross, God announces a cosmic type of deconstruction which incorporates all of creation and, by definition, all of humanity. This deconstruction begins with Jesus’ crucifixion on the cross and its ripples permeate to the ends of the Universe. Whether it be the kingdoms of humanity, the customs of this world or the prevailing cultures which confront the kingdom of God, at the heart of the gospel and through the lens of the cross we observe a process of deconstruction outworked from the fingertips of God himself.

This article will focus predominantly on the symbol of the cross, for the cross is, in many ways, the ultimate symbol of deconstruction. The message and purpose of this wooden cross, which was a symbol of shame, defeat and death, was deconstructed and re-defined through the work of Jesus Christ. Through his death and resurrection Jesus tore down the power, meaning and significance of the cross, turning it wholeheartedly into something new, to become a symbol of life, honour and eternal victory.

Get access to exclusive bonus content & updates: register & sign up to the Premier Unbelievable? newsletter!

A symbol of shame

Ancient Roman society was built on a foundation of societal honour and shame, through which one’s level of societal respect was based on cultural indicators. Things like your family heritage, connections, education and performance all contributed to your level of right-standing in the community. Unlike our modern western culture, your social standing was based less on your individual identity and far more on your performance as part of the social group. You would be publicly honoured if you were in line with the ways of society, and you would be publicly shamed if you were not.

Recognising that honour and shame were baked into the fabric of ancient Rome, we are given a paradigm for understanding the kind of shame that was associated with the cross. It is well-known that at the time of Jesus the cross was considered to be a starkly shameful symbol. The cross was a form of execution which brought about a long, slow death. Crucifixion was often a public spectacle which endured for days. It was a method of execution so shameful that it was reserved for the lowest of the low; for criminals and slaves alike. In fact, it was so shameful that Roman citizens were entirely exempt from crucifixion.

Yet, for some reason, the Messiah chose to go to the cross. He chose to engage with this shame, to take on this shameful identity, by being crucified as an innocent man. He not only approached this symbol of shame but he allowed himself to be publicly shamed upon it. As we read in Hebrews 12:2-3, he “endured the cross, scorning its shame”, taking that shame upon himself so that no-one else would have to do so.

In his sovereignty, Jesus demonstrated a form of divine deconstruction. Through this sacrifice, he deconstructed the shame of the cross, in its place defining the cross as a place where divinity and humanity meet, and where shame was ultimately defeated. By embracing the shame of the cross he took away its power, re-defining its meaning, to the point where the symbol of the cross has become the symbolic centrepiece of the Christian faith. As disciples of Jesus today we define ourselves by the symbol of the cross; no longer a symbol of shame but a symbol of the deconstructing work of Christ.

A symbol of defeat

As one of the most brutal ancient mechanisms of execution, in the ancient world, the cross represented total and final defeat. It was the end of the road. For those who ended up nailed to a cross it meant that they had been defeated.

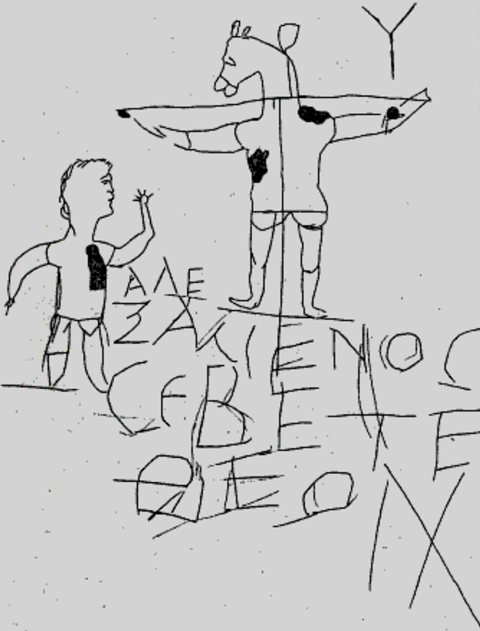

To illustrate this, let us observe The Alexamenos Graffito, which is the earliest surviving image that we have of the crucifixion of Christ, dated to around 200 AD. It consists of a somewhat crude drawing of a man hanging on a cross with the head of an ass. Next to the cross is another figure who has his arm extended to the cross. The words carved next to the image translate as “Alexamenos worships [his] God.”

The Alexamenos Graffito is an image which gives us an insight into the symbol of the cross as a symbol of defeat. It demonstrates the humiliation of the cross, the shame of crucifixion, and it exposes us to a common perception of Christianity at the time: that of the upside-down kingdom that followers of Jesus believed in. How could a God be crucified on a cross? How could you worship someone who was crucified? For surely if your God ends up on a cross, he has been entirely defeated? This gospel message is and always has been one which stands in stark contrast to the cultural narratives of the day.

As the author Philip Yancey writes in his book ‘Where is God When it Hurts?’: “To some, the image of a pale body glimmering on a dark night whispers of defeat.” For those looking upon the cross as Jesus hung there 2,000 years ago, the image would have been one of defeat. For Jesus’ disciples, they would have considered the death of their long-expected Messiah to be a moment of complete defeat.

Yet, in some way, Jesus usurped the power of the cross, turning it from being a symbol of defeat to a symbol of victory. He deconstructed the narrative of defeat that the cross perpetuated and re-defined the cross as a symbol of life in all its fullness.

The ultimate symbol of defeat was, through the work of Jesus, deconstructed and re-defined as a symbol of life. For this cross ultimately brought forth true and eternal life, not just for Jesus but for all of humanity.

A symbol of death

The journey to the cross was a one-way trip; you didn’t come back from the cross alive. Crucifixion was, in obvious ways, a death sentence. It was a method of execution that was designed to prolong suffering for days at a time but which would, ultimately, always end in death. For this reason, the cross became known in the ancient world for being a symbol of death.

For every person crucified, the cross had the final say. And even for Jesus, the cross brought with it the sting of death. As we read in Philippians 2:8: “And being found in appearance as a man, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to death - even death on a cross.” Yet for Jesus, death did not have the final say. “For we know that since Christ was raised from the dead, he cannot die again; death no longer has mastery over him.” (Romans 6:9)

By taking to the cross, embracing death and then rising again, Jesus deconstructed death itself and took away the very essence of death’s power. He defeated death, declaring that it would no longer have the final say, re-defining the cross to become the symbol of true and eternal life. In a divine exchange this symbol which most starkly represented death became a symbol of hope and eternal life.

Today, many churches are decorated with the symbol of the empty cross. For the hope of Christ is a hope which is found in the empty cross: the true and eternal symbol of life in all its fullness. It is in the empty cross that we are grounded in our hope that, for us too, death will not have the final say.

Towards a biblical theology of deconstruction

As we have seen, through the cross Jesus deconstructed the message and the power of the cross. This ancient symbol of shame, defeat and death was replaced by a declaration of honour, victory and life. Jesus turned the meaning of the cross on its head, in doing so giving us a new paradigm for approaching life and relating with God.

Yet, as we reflect upon the cross as the ultimate symbol of deconstruction, we are led to the larger task of journeying towards a biblical theology of deconstruction. For through the lens of the cross we begin to see the whole world in a different way. And we begin to recognise the task that God is calling us to through the power of the Holy Spirit. As Paul tells us in 1 Corinthians 1:18: “For the message of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God.”

Through his work on the cross Jesus gives us an example of what it looks like when the kingdom of God confronts the kingdom of humanity, and we are exposed to a glimpse of what the deconstructing work of God does and will look like, both in this life and the life to come. As disciples of Jesus we are invited into this work of deconstruction, as we seek the upside-down kingdom of God and as we pursue the presence and power of God in our day-to-day lives.

As we encounter the injustices of our societies, the evils of our world and the sufferings of our neighbours, we are invited into the godly work of deconstruction. Yet we must even look beyond that. For just as Jesus rose from the dead and ushered in a new hope of eternal life, we are equally tasked with the work of reconstruction and restoration in the light of Christ and through the lens of the cross.

Timothy James is a theological researcher and writer, and an undergraduate tutor at St Mellitus College, London. Tim is also the founder of Access Theology: a start-up organisation which is committed to equipping followers of Jesus and resourcing churches through the creation and distribution of accessible theological resources.